On January 1, 1925, astronomer Edwin Hubble completely changed the way we see the universe and our place in it. The discovery came from looking through the world’s largest telescope at the time, located on a remote mountaintop in the Angeles National Forest. Not only was the world changing, but so was life for Hubble, who became one of the most recognizable names in astronomy. Today, even the most casual space watcher is likely familiar with his name.

But Hubble’s breakthrough is probably (at least in part) due to the efforts of a little-known astronomer: George Ellery Hale, a man determined to build the world’s largest telescope on a mountaintop high above of all places, the then-burgeoning city of Los Angeles.

A man’s quest to build large telescopes

Hale’s obsession with building ever-larger telescopes began on a trip to the Bay Area’s Lick Observatory in 1890, which housed a 36-inch refractor, then the largest telescope on Earth. Within a few years, Hale had raised the funds for a 40-inch telescope of his own, to be located at the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin, where he was director.

Article continues below this advertisement

In 1903, Hale visited Mount Wilson, a 5,715-foot peak in the San Gabriel Mountains above Pasadena, and was enamored with the prospect of a mountaintop observatory in California’s milder climate. “Mountaintop Isolation . . . gave him a strong appeal [Hale’s] his pioneering spirit and his joy in discovering the ever-changing beauties of nature,” wrote one of the observatory’s first staff members at the time.

Photograph taken in the West Galleries of the Science Museum, London, showing George Ellery Hale standing next to the 6-foot mirror of the Great Rosse Telescope.

Science and Society Image Library/SSPL via Getty ImagesHale moved a solar telescope from Yerkes Observatory west to Mount Wilson, and the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory (now known as the Mount Wilson Observatory) was formed in 1904.

Article continues below this advertisement

Hale soon set to work building an even larger telescope on Mount Wilson than he had in Wisconsin, and in December 1908, a new 60-inch telescope was used for the first time, dwarfing the Lick Observatory he had previously encountered. first seen almost 20 years ago. The figure 60 inches refers to the diameter of the circular glass disc used to collect and reflect light from space; the more inches, the more observers can clearly see and document.

Hale was a prolific fundraiser, networking and advocating for more funding for astronomy with some of the wealthiest magnates of the era, including Andrew Carnegie, so it was only natural that before long, Hale had raised enough capital to finance a telescope larger than 60 inches. In fact, Hale had begun building his next, even larger telescope before the 60-inch one was up and running.

One of 41 photographic bromide prints relating to and showing various stages in the construction of the 100-inch Hooker Reflecting Telescope at Mount Wilson, California. This view shows a mid-section of the telescope tube reaching the observatory, 1917.

Science and Society Image Library/Getty Images

One of 41 photographic bromide prints relating to and showing various stages in the construction of the 100-inch Hooker Reflecting Telescope at Mount Wilson, California. This view shows the side parts of the telescope’s polar axis being mounted on the observatory’s dome, 1917.

Science and Society Image Library/Getty ImagesEfforts to complete a new 100-inch telescope dragged on for more than a decade, amid much doubt that it would work and a stressful fundraising storm from Hale, who fell into ill health. Concerned about Hale’s constant stress over the telescope, his wife once wrote, “I wish that glass was at the bottom of the ocean.”

Article continues below this advertisement

In 1917, with the ocean far in the distance, Hale’s 100-inch mirror was driven up the windy mountain roads to the Mount Wilson Observatory by a truck traveling about 1 mph. Hundreds of men accompanied the truck to protect the precious glass from falling down the mountain.

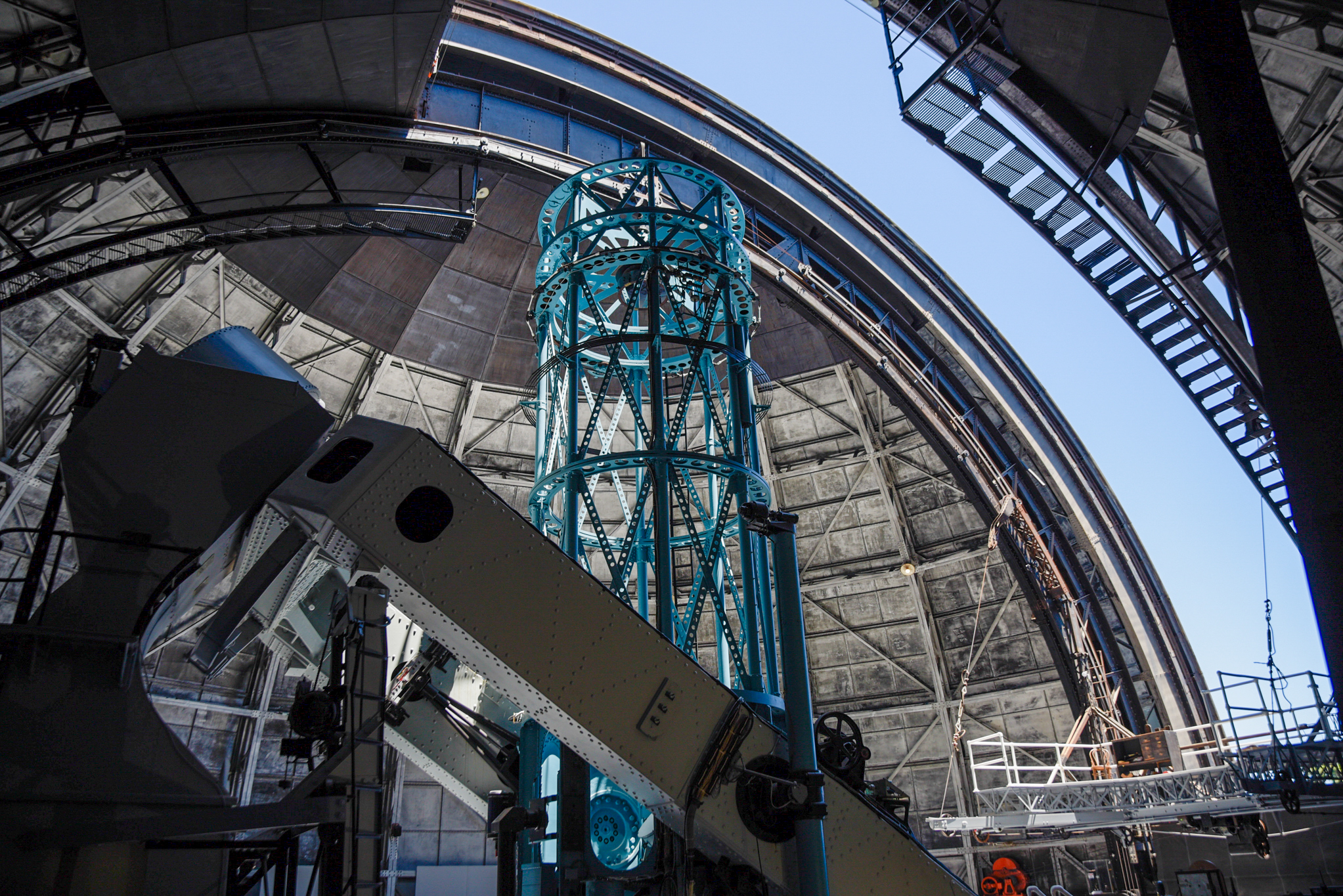

The dome opens at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles on June 13, 2024.

Ashley Hayes-Stone/SFGATEOnce placed inside its large white dome, the mirror was ready for its first viewing. A crowd of astronomers and others gathered to try to catch a glimpse of Jupiter through the telescope. Instead, the view through the eyepiece was distorted, showing “six or seven images partially overlapping irregularly and filling most of the eyepiece,” wrote Walter Adams, the observatory’s assistant director. But the problem was simple: since the dome remained open during the day, the mirror became very hot, expanding the surface of the glass and distorting the resulting image. Hale and Adams returned to the dome at 3 a.m. and saw their first clear view of the stars through the giant telescope.

Solving the issue of distant “island universes”.

Mount Wilson’s large, state-of-the-art telescopes drew Edwin Hubble to the observatory in 1919, where he would go on to make one of his greatest discoveries.

Article continues below this advertisement

The 150-foot solar tower stands at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles on June 13, 2024.

Ashley Hayes-Stone/SFGATEAt the time, the astronomy community was focused on the question of “spiral nebulae”, which look like wheels of star clouds in the sky, and whether these spirals were part of our Milky Way galaxy or their own “island universes”.

Using the 100-inch telescope, Hubble searched for stars of varying brightness in one such area, the Andromeda Nebula, where he found a type of star that was useful in determining distance. By finding dozens of these stars in various spiral nebulae, and by focusing on individual stars rather than just looking at the spirals as a whole, Hubble eventually determined that the nebulae were too far away to be within the Milky Way.

In that discovery, the whole way we think about the universe changed. There was no galaxy, dominated by the Milky Way and surrounded by the more distant spiral nebula, but many distant galaxies besides the Milky Way. The realization greatly expanded our understanding of the size of the universe.

Article continues below this advertisement

A wide view of the 60-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles on June 13, 2024.

Ashley Hayes-Stone/SFGATE

Photographs of Edwin Hubble, left, and Henrietta Leavitt are on display at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles on June 13, 2024.

Ashley Hayes-Stone/SFGATEHubble’s findings “proved beyond doubt that the nebulae were external galaxies comparable to our own. He opened the last frontier of astronomy and gave, for the first time, the exact conceptual value of the universe. Galaxies are the units of matter that define the grain structure of the universe,” wrote Allan Sandage in the Hubble Atlas of Galaxies.

“The whole proceeding admirably illustrates how the scientist works. He has an open mind. He is always ready to adopt the theory which the facts seem best to support. He is ready to change his opinion when new facts justify it,” wrote a reporter in the Whittier News shortly after the revelation.

Article continues below this advertisement

A final view of the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles on June 13, 2024.

Ashley Hayes-Stone/SFGATEIn the following decades, light pollution from the growing city of Los Angeles made Mount Wilson a less ideal location for new astronomical discoveries, and the latest large field instruments were built in places with darker skies such as San Diego and, later, the Big Island of Hawaii. where the Keck Observatory’s twin telescopes are each 32.8 feet in diameter.

Telescopes for people

Today, the white domes of Mount Wilson’s telescopes are still visible from Highway 210 below on clear days, while the forests at the summit are fairly quiet most days except for day hikers, hikers and the occasional afternoon concert. Nods to the observatory’s importance are present throughout the winding objects, from a small sign reading “EINSTEIN WAS HERE! January 29, 1931” attached to the wall inside the 150-foot solar telescope to the cabinet with Hubble’s name above it below the 100-inch telescope .

Article continues below this advertisement

Left: Astronomer Edwin Hubble. Right: German-born physicist Albert Einstein visiting Mount Wilson Observatory, California, which at the time operated the world’s largest telescope, 1931. Among the group are American astronomers Edwin Hubble (back, second from left), Walter Sydney Adams (center, in hat), and William Wallace Campbell.

New York Times/brand images/Getty ImagesThe observatory is now run primarily by Mount Wilson Institute volunteers, with a mission to connect the public with the observatory space. This mission has included launching public events under the 100-inch telescope, holding lectures, facilitating group rentals of the 60-inch and 100-inch telescopes, and hosting public ticket nights, when individuals can purchase a ticket and view the telescopes. The observatory still looms over Los Angeles after narrowly surviving the 2020 Bobcat fire, which scorched surrounding parts of the Angeles National Forest and came within a few hundred meters of the famous telescopes.

And while they’re no longer the largest in the world, the observatory’s telescopes still hold a grand claim to fame that Hale can be proud of. According to the observatory, the telescopes now hold the title of “the largest telescopes in the world that are available for public use.”

More Los Angeles coverage